Overweight? Blame Energy Balance Theory and Dietary Guidelines

Notes for 3/22/2022 Podcast/video discussion with Marina (On YouTube: Discussing Nutrition-Goodman Study.

M: Greg, what’s new in your world of nutrition and public health?

G: The Goodman Institute released Brief Analysis 142: Did the Government Make Us Fat? which draws from peer-reviewed research explaining errors in the “energy balance theory of obesity.” Many in the U.S. and Canada were overweight before the pandemic and lockdowns, and many now heavier and looking to lose weight. Generally people are advised by public health officials and doctors to: “eat less and exercise more.”

This “calories in; calories out” theory of obesity sounds reasonable but is misleading on manylevels, and unhelpful, even harmful, for most. People who gain unwanted weight usually have a hormonal condition called insulin resistance. So it’s best for them to recover metabolic health through dietary changes. Weight loss usually follows naturally. This doesn’t mean to “eat less” and go hungry, instead the better advice is to Eat Different. But first, how do we measure metabolic health?

Tests can measure blood glucose levels and hemoglobin A1C (a measure of average blood sugar levels over three months). We can also use inexpensive scales to measure body composition as well as weight.

While waiting for a blood test, a first step is to just… eat less carbohydrates. Sugar cravings are a challenge but most can “reset” their taste buds with a three days sugar fast. It’s amazing but desserts and chocolate bars will taste better with less sugar. There is little or no sacrifice in all this, just some patience to prepare for and enter a healthier nutritional landscape.

Misguided federal dietary guidelines pushed for reducing fat, and called on food companies to develop hundreds of low-fat foods and drinks (at the time researchers believed saturated fats caused heart disease). But these new low-fat foods contained more carbohydrates and usually more sugar.

Tastes vary, of course, but people have long been told oatmeal for breakfast is somehow healthier than eggs and bacon. That turns out not to true. Most research shows health benefits from reducing carbohydrates, especially processed foods with seed oils (marketed as vegetable oils) made from industrially processed seeds (PUFAs.)

M: So you are saying that overweight people should go on a low-carb diet? I thought we had agreed that we were not providing medical advice since neither of us are doctors or credentialed nutritionists.

G: Well, I’m offering “advice from a friend” for Normal Nutrition the title of our site. This draws from a comment Nina Teicholz makes. Teicholz, a science journalist, is author of The Big Fat Surprise, a deeply-researched history of nutrition science over decades. She notes what people call a “low-carb” diet today is just the average diet for Americans and Europeans before the federal push for Food Pyramids and Food Plates to reduce fat, especially saturated fat.

M: for our listeners or viewers, what are low-fat or low-carb diets, how are they defined?

Federal guidelines listed online: The U.S. Dietary Guidelines say 45 to 65 percent of your calories should come from carbohydrates, while 20 to 35 percent should come from total fat. You should also get 10 to 35 percent of your calories from protein.

So a “low carb” diet could be just less than that 45-65%. Which is, again, high by historical standards, at least for Europeans and Americans.

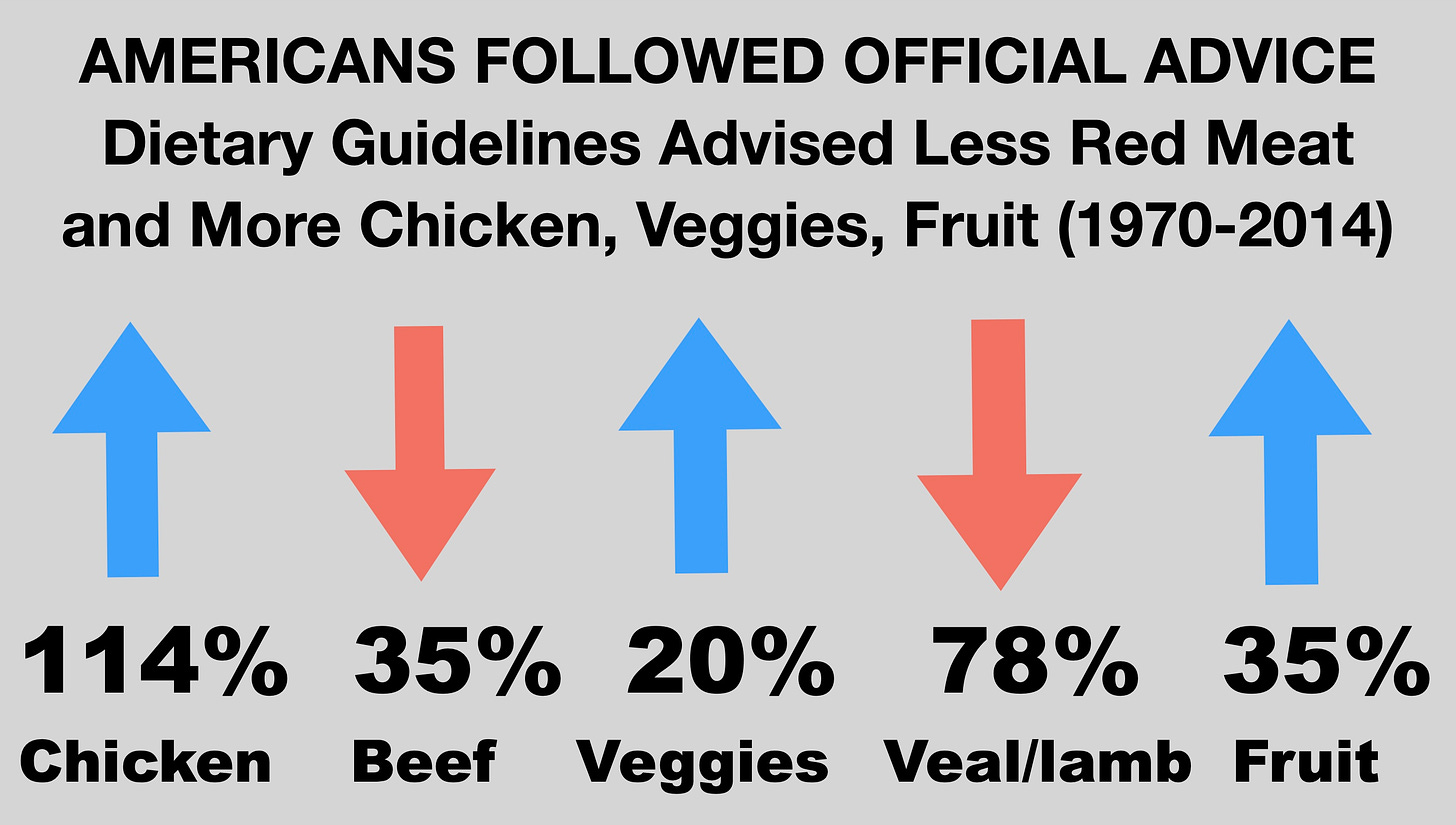

Since 1970s beef, chicken, and pork in US have been bred to have much less fat, so Americans have shifted to leaner meats, and shifted especially to chicken, a white meat, from beef a red meat. Americans were encouraged to eat more grains, vegetables and fruit, and they have.

Saturated fat in US diets fell a lot and polyunsaturated fat (vegetable or seed oils) increased.

M: So people can read the Goodman Institute paper, or read past Normal Nutrition posts that cover much of your analysis. What else nutrition and diet related have you been reading and researching?

G: Two areas I’d like to briefly discuss. First: what’s called the obesity and diabetes epidemic expanded after 1980. Dieting expanded to, along with waistlines. Obesity was under 15% of Americans in 1980 and nearly 40% by 2016 (Canada at 11% in 1980 and 31% by 2016).

Unfortunately with language, the word “diet” has two meanings. One is for what we consume, our diet. But another meaning is to consciously choose to constrain or control what we eat, that is, to “go on a diet.” And that’s a different and unnatural step, and usually a problem. A previous post highlighted anti-diet and intuitive eating books critical of calorie counting and the diet industry.

[Though not discussed in video, notes below on dieting and central planning…]

Market economists explain why top-down control of the economy fails. The central planners can’t know enough to direct millions of producers and consumers across the economy. People are not chess pieces to be moved about in service of central planners.

Similarly when people go on a diet, they are trying to suppress intuitive patterns and processes. Our body, our internal organs and metabolic system, responds to local biochemical signals and conditions that we don’t know about as we try to consciously plan our eating patterns. It’s like trying to walk by thinking through each step to place each foot ahead and lift each foot behind. Most of us practice intuitive walking. So why not trust intuitive eating?

Nutrition researchers who advocate intuitive eating and are critical of dieting cycles emphasize that it’s natural and healthy to eat when hungry and to eat until we are not hungry. Of course habits matter and can be guided, but for people under the influence of “central dietary planning,” the rules are to consciously count calories and stop eating before we are full (before satiety): to just “eat less.” But that creates various internal metabolic challenges and unintended responses.

Natural hunger and cravings are influenced by the foods we choose to eat: protein and healthy fat make people feel full faster and longer. Consuming carbohydrates, especially with unnatural (processed) mix of carbs and fat, people tend to eat a more and be hungry sooner.

So the low-fat push by federal dietary planners led people to eat more carbohydrates, more often and gain weight, then go on diets that backfired (thanks to the misguided “energy balance theory of obesity” discussed above and at length in Did The Government Make Us Fat?).